This list is updated monthly with new “best of the year”–worthy titles.

In the first three months of the year, all eyes are often on the films that came before — the contenders that dominated the fall, vying for Academy Awards. But while studios usually save their glitziest, prestige-iest films for the horse race, there are, in fact, many movies worth your time and attention that have come to us in late winter and spring. Some might be epic-scale blockbusters (Dune: Part Two), but most of this year’s best so far are smaller films, released without a major studio’s marketing budget. One is a violent swashbuckling-adventure film, and another is a brilliant comedy as bleak as it is funny. Two mark the debuts of commanding new voices in film; another is a bittersweet good-bye to a great composer and musician. All will reward you for seeking them out. Here, the best of the many dozens of movies we’ve seen this year so far.

Movies are listed by U.S. release date, starting with the most recent titles.

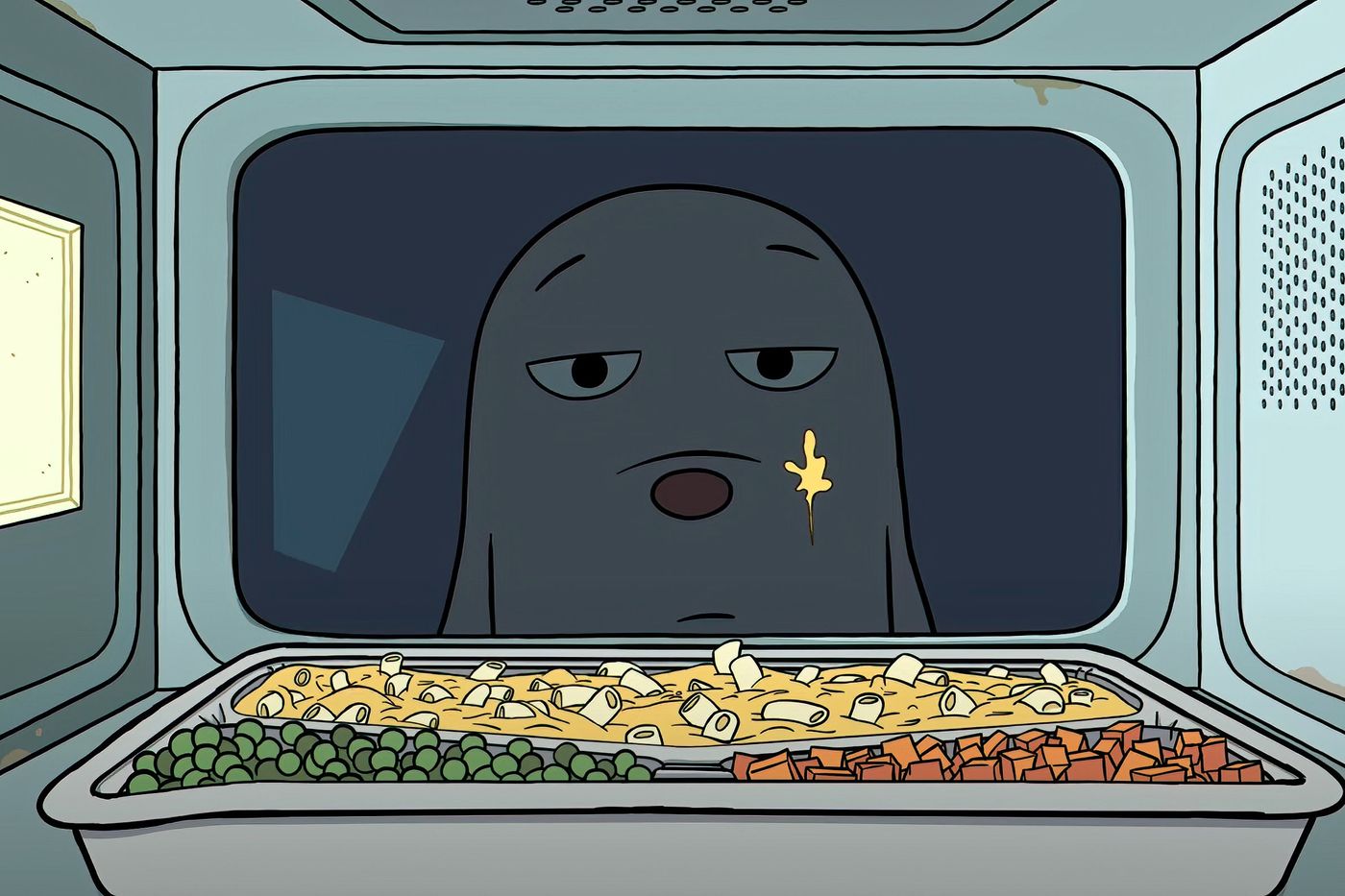

Robot Dreams

Pablo Berger’s animated adaptation of Sara Varon’s 2007 book, the story of a dog and its pet robot in mid-1980s New York, was nominated for the Best Animated Feature Oscar earlier this year. But its hand-drawn, fablelike style, along with its entrancing and melancholy beauty, feels old-fashioned in a contemporary animation world largely defined by clutter and smarm. With zero dialogue, the film follows a lonely dog (known simply as Dog) who purchases a robot companion by mail. Dog assembles Robot, and the two of them proceed to spend a wonderful summer in the overcrowded, sweaty city. But then they’re suddenly separated, and their lives diverge. The always awkward Dog finds another companion while Robot has encounters with the rest of the world that are sometimes dreams, sometimes real. Though the story seems to take place over the course of one year, we see New York change around these characters as well. Watching Robot Dreams, we find ourselves reflecting on how our own lives have changed as we’ve grown: the friends we’ve left behind but haven’t forgotten, the cities that have transformed around us, the wisdom we’ve accrued, and all the ways in which we’re still slightly damaged from all that living. —Bilge Ebiri

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Robot Dreams.

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

A prequel, a revenge tale, and even something of a bildungsroman, George Miller’s prequel to Mad Max: Fury Road follows the travails of the young Furiosa (played as a child by Alyla Browne, an adult by Anya Taylor-Joy) as she’s kidnapped by a motorcycle warlord named Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) and later traded off to Immortan Joe (the villain of Fury Road, here played by Lachy Hulme, in slightly younger, less pustule-filled form). Until now, the characters in the Mad Max films — yes, even the children — have arrived mostly fully formed, their minds and attitudes shaped by this dead world. Here, however, we watch a bright, young innocent lose everything that has ever meant anything to her, and her heart hardens. A pall of hopelessness hangs over the movie as we absorb the lessons of the wasteland along with our heroine. But the film is also thrilling in its own right. Action sequences charge forward and build and build, casually leaving all manner of bodies in their wake. The director also indulges his fondness for yarn-spinning, as he did in his previous film, the masterful Three Thousand Years of Longing (2022). It might not be a huge hit, but it’s nice to know that, after all these years, George Miller seems determined to stay true to his mad self. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga; Ebiri’s close look at the ending; Fran Hoepfner’s chat with actor Tom Burke; and James Grebey on Dementus’s cape.

Hit Man

“How many of you really know yourselves?” Philosophy lecturer Gary Johnson (Glen Powell) posits this question early on in Richard Linklater’s Hit Man. “What if your self is a construction, an illusion … a role you’ve been playing since the day you were born?” It turns out that he’s about to become a walking answer to the question, as this amiable, bird-watching Everyman pretends to be an assassin for the New Orleans police department’s sting operations. As a fake hit man, Gary is effectively playing a figure out of our collective imagination — and that liberates him. He can make up the character as he sees fit because the people he’s playing quite simply don’t exist. Hit Man works simultaneously as an indulgence in and a deconstruction of the basic transaction of stardom: It presents us with a guy we can never be, then makes us believe for a moment that we can be him, even as it tells us that such a guy doesn’t exist in the first place. If Glen Powell’s not already a star, this picture might well make him one. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Hit Man.

Kidnapped

A number of filmmakers, including Steven Spielberg, have over the years attempted to adapt the remarkable true story of Edgardo Mortara, a young Jewish boy in Bologna who was taken from his family by papal authorities in the mid-19th century and raised as a Catholic. But it’s perhaps appropriate that the film was finally made by the legendary Italian director Marco Bellocchio, a man who has spent his entire career questioning the power of social institutions. Bellocchio is also a master of depicting the way madness functions in families as both an external and internal force. In the sweeping, melodramatic Kidnapped, he shows not just what happened to Edgar, but also the toll it took on his family. It’s a multicharacter saga that is at once thoroughly entertaining and thoroughly terrifying. —B.E.

I Saw the TV Glow

Haunting, unsettling, and so emotionally raw it feels like an open wound, Jane Schoenbrun’s film is an exploration of dysphoria, suburban isolation, and the imperfect refuge that is fandom.It’s easy to see traces of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Twin Peaks in The Pink Opaque, the dreamy supernatural drama that outcasts Owen (Justice Smith) and Maddy (Brigette Lundy-Paine) fixate on and bond over in high school. But while the show’s mythology seeps into their lives and serves as a metaphor Owen steadfastly refuses to acknowledge, the most compelling moment is the one when, a little older, Owen revisits the source of his obsession and finds that it’s nowhere near as compelling as it was in his memory. Pop culture can serve as a life raft and a refuge, but Schoenbrun’s film makes it achingly clear that Owen has to take the steps necessary to save himself in the real world. —Alison Willmore

➽ Read Alison Willmore’s full review of I Saw the TV Glow; Esther Zuckerman’s interview with filmmaker Jane Schoenbrun; and Rachel Handler’s interview with Caroline Polachek about her song for the soundtrack.

Gasoline Rainbow

The latest movie from the Ross brothers is another freewheeling creation inhabiting a limbo between fiction and non, where first-time cast members play characters inspired by — but not confined to — their own lives, improvising scenes within the boundaries of a scripted scenario. In Gasoline Rainbow, the story takes the form of a road trip to the coast embarked on by a group of five longtime friends fresh out of high school, though the journey is less about the destination than it is the picaresque adventures the group experiences along the way, as the kids meet rail-hopping crust punks, nautically-inclined skateboarders, and Lord of the Rings-loving metalheads. It’s ragged and exhilarating, like taking a hit right off the feeling of being 18 and sure your true self is out there, waiting to be discovered. —A.W.

➽ Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Gasoline Rainbow.

Evil Does Not Exist

The quietly wandering, elliptical quality of the early scenes inRyūsuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist might feel like a departure from the Drive My Car director’s recent and best-known work. We spend time with widower Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), who lives with his daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) and makes a living doing odd jobs in and around the village of Mizubiki, chopping firewood, harvesting plants, collecting water from the springs for the local ramen joint. The peaceful life of this village is interrupted with the arrival of two representatives from a talent agency that’s planning to open a “glamping” business nearby. In the film’s most bravura scene, a presentation to a group of locals devolves into an extended confrontation when the villagers begin to ask questions about a variety of concerns, most notably the placement of the site’s new septic tank, which is too small for the number of expected customers and also upstream from the town’s fresh-water source. Evil Does Not Exist rings unnervingly true in its particulars, from the bizarre bedfellows created by modern capitalism to the quiet contempt with which city folk treat poorer villagers. But Hamaguchi also doesn’t give us obvious villains, instead portraying different people from different worlds, each trying to survive in their own way. Even so, in its own discreet, modest way, the film leaves us with a haunting sense of a personal and ecological apocalypse. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Evil Does Not Exist and Rachel Handler’s dispatch from the Venice Film Festival.

The Fall Guy

David Leitch’s action-comedy mystery romance set in the world of stunt professionals is an act of pure movie love, mixing and matching genres while tossing off in-jokes and references to its illustrious (and not-so-illustrious) forebears. Ryan Gosling, whose comedic talents were criminally undervalued until last year’s runaway hit Barbie, gets to flex them again here, bringing his deadpan, affably dim charm to the role of Colt Seavers, a hot-shot stunt double for megawatt movie star Tom Ryder (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). After an accident seems to end his career, a forlorn Colt gets a call to come perform a stunt on the Sydney set of a new flick being directed by Jody Moreno (Emily Blunt), the woman he once loved, and is sucked into a shaggy-dog missing-persons case. The stunts are spectacular and Gosling is very funny, but maybe the most surprising thing about the film is how genuinely romantic it is. Blunt and Gosling have splendid chemistry — the kind of onscreen magnetism shared by people who are not just insanely hot but also simply know how to look at each other. The film invests us in wanting Colt and Jody to get back together; we’re willing to accept any ridiculous situation so long as it reunites them. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of The Fall Guy; Ebiri’s behind-the-scenes look with the stunt team; and Ebiri’s conversation with director David Leitch.

Alam

The conversations around Palestine and Israel often don’t leave much room for nuance, but Firaz Khoury’s moving coming-of-age film offers a corrective. Not everyone realizes that there are Palestinians in Israel, living in Palestinian neighborhoods, going to schools with Palestinian teachers — but they’re taught Israeli history, seen from Israel’s perspective, all under an Israeli flag (alam is an Arabic word for banner). So they learn about Israel’s battle for independence, even though for them it’s known as the Nakba — the “catastrophe,” in which their families were displaced in 1948. In Alam, a group of middle-class students wrestles with romance, authority, and political awakening in the days leading up to Israel’s Independence Day. These are kids with means and prospects, with families and teachers who want them to keep their hands clean. To them, the political (and physical) battles being waged over their homeland sometimes seem abstract, and yet they can’t help but look for ways to be involved. This is a marvelous, mesmerizing film that offers no easy answers. —Bilge Ebiri

Challengers

It’s sexy, it’s sweaty, it’s mean, and it’s just so fun — Luca Guadagnino’s tennis romance is one of the year’s treats, a film that revels in the baby-movie-star qualities of leads Mike Faist, Josh O’Connor, and Zendaya, allowing them to be larger than life even as their characters act hopelessly petty. A BDSM drama as told via sporting events, Challengers manages to make tennis look hot and to make the romantic maneuvers among the three characters into athletic competitions. All that, an oomph-oomph score, and a finale that includes shots from the POV of the ball? What did we do to deserve this, and how do we do it again? —Alison Willmore

➽Read Angelica Jade Bastién’s review of Challengers, Matt Zoller Seitz’s review of Zendaya’s movie performance, and Joe Reid’s explanation of who won in the ending scene.

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed

Joanna Arnow’s feature directing debut is an unclassifiable deadpan comedy about a Brooklyn woman, Ann (played by Arnow herself), whose entire life seems to revolve around humiliation: She’s in a sub-dom relationship with an older man whose reluctant, disaffected approach to her needs might be part of their whole thing; she endures constant awkward conversations with her parents (played by the director’s own parents); she’s completely ignored at work even when she’s being given an award. There’s a surreal quality to the film, and yet it all feels so true. Arnow has captured something about the authentic and mortifying absurdity of modern life — and she’s done it in a thoroughly entertaining way. Her filmmaking style is episodic, but not in the exhausting, indulgent style of so many other plotless dramedies: Her vignettes vary from extended sequences to comically brief snippets, giving the picture a unique and irresistible cadence. —B.E.

Civil War

What makes Alex Garland’s controversial new film so diabolically clever is the way that it both revels in and abhors our fascination with the idea of America as a battlefield. The film is set in what appears to be the present, but in this version of the present a combination of strongman tactics and secessionist movements have fractured the United States into multiple armed, politically unspecified factions. Smoke rises from cities; the highways are filled with walls of wrecked cars; suicide bombers dive into a crowd lined up for water rations; death squads, snipers, and mass graves dot the countryside. How we got here, or what these people are fighting over, is mostly meaningless to the journalists covering this war, who gather in hotel bars, get drunk, and loudly yuk it up with the jacked-up bonhomie we might recognize from movies set in foreign lands like The Killing Fields, Under Fire, and Salvador. They’re mostly numb to the horrors they’re chronicling. The movie’s lack of a political point of view has received some understandable criticism, but the conceit here is to depict Americans acting the way we’ve seen people act in other international conflicts, be it Vietnam or Lebanon or the former Yugoslavia or Iraq or Gaza or … well, the list goes on. It doesn’t want to make us feel so much as it wants us to ask why we don’t feel anything. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Civil War; Matt Zoller Seitz’s interview with director Alex Garland; and Roxana Hadadi’s essay on the movie’s final shot.

In Flames

Could we call In Flames, Pakistan’s submission for last year’s Best International Film Oscar, a horror movie? How could we not? It looks at the life of a young Karachi woman whose world is upended after the death of her father: Men stare at her, attack her, obsess over her, ignore her. The prying eyes of a patriarchal society see her as both victim and prey. A brief, seemingly promising relationship ends in tragedy. She’s pursued by haunting visions as she begins to lose the line between reality and illusion. Director Zarrar Khan depicts both supernatural shocks and real-life terrors with the same jump-scare-laced bravado but does so without ever shortchanging the very real drama at the film’s heart. —B.E.

The Beast

Bertrand Bonello’s sci-fi epic is Henry James by way of David Lynch, a beguiling, slippery creation that spans three time periods and settings, and that manages to constantly surprise and unsettle. As Gabrielle, Léa Seydoux is a tragic costume-drama heroine, a stalkee in a horror film, and a frustrated seeker in an aloof futurescape, and she manages to create a sense of continuity over these very different lives, into which Louis (George MacKay) inevitably appears. The Beast is wistful, scary, and unsettling, and more than anything, it’s a big swing — a movie about being afraid of vulnerability that is itself fearless. —A.W.

➽ Read Alison Willmore’s full review of The Beast.

The First Omen

Directed by Arkasha Stevenson, this prequel to 1976’s The Omen is another modern horror movie that speaks to our current moment even as it tells a fantastical story rooted in the past. In this case, the year is 1971, and young novitiate Margaret Daino (Nell Tiger Free) has just arrived in a turbulent Rome to work at an orphanage. She becomes intrigued by the odd, introverted Carlita Skianna (Nicole Sorace), one of the orphans. She sees something of herself in the girl and tries to forge a bond with her. Then a rogue priest warns her that Carlita might have been bred by the church specifically to give birth to the Anti-Christ — this is, after all, an Omen movie — and our protagonist becomes determined to save the girl. The film will surely leave you with more questions than it answers, but like the best studio horror directors, Stevenson understands that we’re not here for logic. The movie is soaked in style and mood with images that are both textured and shocking and that tap into tantalizingly visceral fears. If horror is all about loss of control, about feelings of helplessness conjured in the audience to reflect the helplessness of the characters, then this is a true horror film.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of The First Omen.

La Chimera

Alice Rohrwacher’s film follows Arthur Harrison (Josh O’Connor), a strange man with a strange gift for robbing graves, finding and lifting the antique knickknacks the ancient Etruscans of central Italy used to bury with their dead. A former archeologist, he seems haunted by his own exploits, and this occasionally rambling, often gorgeous film’s queasy dream logic suggests that we’re watching a man halfway between this world and the next, struggling to find his place. Rohrwacher, one of Italy’s foremost filmmakers, makes earthy movies with a dash of what we might call magical realism. The performances are naturalistic, the location shooting authentic and ground level, but the stories often hover on the edge of fantasy. The director fills the picture with folk ballads, naif art, playful asides to the camera, and bursts of sped-up slapstick, giving it all the quality of a ramshackle operetta. But O’Connor’s concave, melancholy demeanor undercuts the picture’s levity, likely by design: The more the film goes on, and the more fanciful it becomes, the more Arthur seems unable to reconcile himself to the world around him. He’s a sad, walking embodiment of the notion that those who spend their time worrying about the next life will never feel peace in this one. —B.E.

➽Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of La Chimera.

Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World

Caustic and brilliant, Radu Jude’s latest is a comedy about the terrible absurdity of life under late capitalism that includes among its wide-ranging reference points classical haiku, Goethe, the German schlockmeister Uwe Boll, and a series of profane TikToks records by its main character, an overworked PA named Angela (Ilinca Manolache). Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World consists primarily of Angela’s encounters as she drives around auditioning possible subjects for a company employee safety video, a worker-blaming production made even more absurdly bleak by the fact that Angela has been putting in such long hours she’s in danger of falling asleep on the road. But woven in, brilliantly, are clips from a communist-era film about a female taxi driver, also named Angela (Dorina Lazar), whose state-sanction dramas under the Ceaușescu regime provide a counterpoint to the present day Angela’s gig economy life, until the two characters converge for the final act, which involves the shooting of the corporate production, and is one of the most blackley funny sequences you’ll see this year. —A.W.

➽Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World.

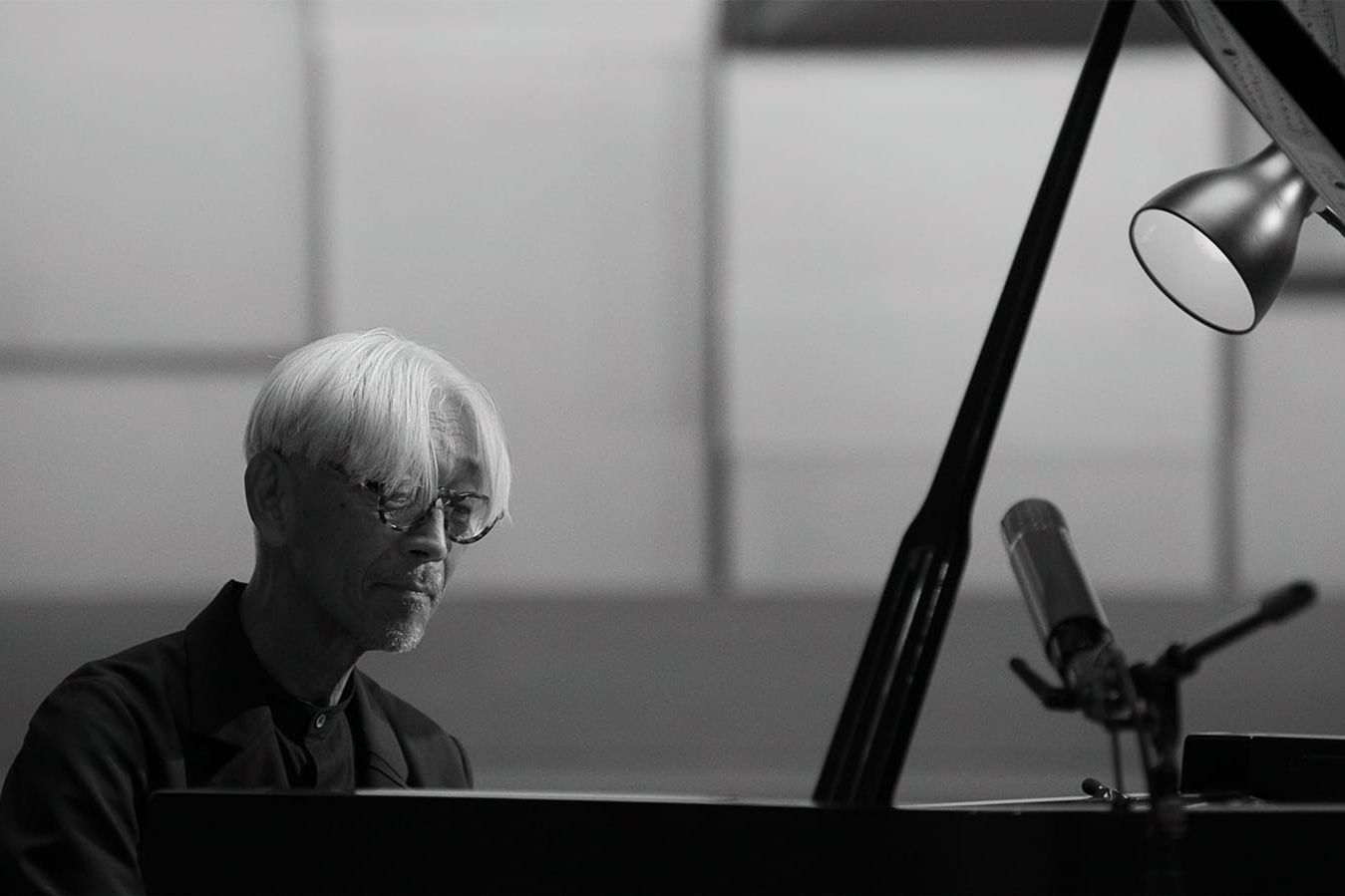

Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus

A few months before he died in March 2023, Ryuichi Sakamoto recorded what he himself suspected might be his final solo concert. It had been created across a few days out of pre-recorded segments that were then assembled and streamed around the world. An expanded version of that concert now exists as a feature film, directed by the late musician’s son, Neo Sora. And it’s a moving, spare, and self-reflective work. Sakamoto was a savvy and thoughtful performer, always aware of his audience and in playful conversation with them. Now, as he communes with his music, we feel like we might be intruding on a private requiem. He doesn’t seem particularly frail during this performance. The fragility lies in the music, in the vulnerability with which he plays it, and in the austere cinematic presentation. The shimmering black-and-white photography and elegant camera moves heighten the intimacy of the performance. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Ryuichi Sakamoto:Opus.

Dune: Part Two

If the first Dune was Timothée Chalamet’s movie, the second belongs to Zendaya, and it’s better and more emotionally accessible for it. Denis Villeneuve’s Frank Herbert adaptation continues to be a spectacular and genuinely alien epic about genetically engineered messiah figures, space witches, massive sandworms, and BDSM-inflected goth fascist planets. But it’s Zendaya’s character, the Fremen warrior Chani, who provides the film’s heart, as a fierce-hearted rebel who’s won over by Chalamet’s Paul despite knowing better, and despite being aware that he’s saying all the right things to win her community to his side for what may be his own purposes. Dune: Part Two has incredible sweep, but it also manages to have recognizable human drama, and that comes entirely from Chani’s perspective as the representative of a people whose own desires are forever subsumed by the machinations of much larger powers. —A.W.

➽ Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Dune: Part Two; Matt Zoller Seitz’s behind-the-scenes look with cinematographer Greig Fraser; and Roxana Hadadi’s analysis of the ending.

Shayda

Noora Niasari’s debut is based on her own childhood experiences, which is evident from the tangibility of its details, but also from the poignant sense that it’s a film about revisiting turbulent young memories with the distance and knowledge of an adult. Holy Spider’s Zar Amir Ebrahimi gives an astounding performance as the title character, an Iranian immigrant in Australia who’s fled an abusive marriage and brought along the young daughter, Mona (Selina Zahednia), that she’s terrified will be taken from her. Shayda deftly lays out the dynamics of the womens’ shelter, and of the local Iranian enclave, pitching its story of escape as a kind of intimate thriller in which Shayda must try to create a sense of normalcy and safety for her child while never being able to let her own guard down. —A.W.

Io Capitano

The Italian director Matteo Garrone likes to fuse the topical with the fanciful, and in this modern-day tale of the refugee crisis, he’s made one of his more shattering films. It follows the journey of two Senegalese cousins, Seydou (Seydou Sarr) and Moussa (Moustapha Fall), who set off for Europe and find themselves confronted along the way with a variety of monstrous incidents, which feel at times like terrifying images out of an old storybook. Garrone mixes magical realism, epic sweep, and gruesome horror in a story that’s been built out of the experiences of real people who’ve made this journey. But he’s not interested in alarmism. His protagonists aren’t desperate to flee any kind of abject poverty or strife — they simply want to travel to Europe, the same way that First World youths have sought to see the world for decades, even centuries. That’s maybe the most novel (and heartbreaking) aspect of Io Capitano. It rejects the idea of its heroes as solely victims, instead placing them in a grander, nobler tradition of exploration and curiosity. In doing so, it asks an implicit, and pointed, question: Why don’t we in “the West” also see them in this light?

The Promised Land

Mads Mikkelsen is a phenomenally skilled actor, but he’s also clearly the kind of performer who understands the value of a good, cold, hard stare. This makes him uniquely well-suited for the role of Captain Ludvig Kahlen, an impoverished, stoic Danish war veteran who sets out in the mid-18th century to try and tame the Jutland Heath, a huge and forbidding area where no crop can grow and where lawlessness reigns. The Danish title of the film, Bastarden, translates as “the bastard,” and could be both a literal and spiritual description of Kahlen. He was born to an unwed servant, and he is a tough, at times heartless taskmaster. As he learns that he has to learn to rely on others in order to survive, Kahlen also finds himself at odds with a local landowner, a preening and sadistic aristocrat named Frederik de Schinkel. And so, The Promised Land transforms from a stately and lyrical tale of rural survival to something more primal and intense; think Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven crossed with Michael Caton-Jones’s Rob Roy, only with more scenes of people being boiled alive. —B.E.

➽ Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of The Promised Land.

Pictures of Ghosts

This terrifically bittersweet documentary from Bacurau’s Kleber Mendonça Filho is part memoir, part history of the director’s hometown of Recife, and part meditation on the nature of photography that outlasts the subjects it has captured. But more than anything, it’s a tribute to a life shaped by cinema that manages to avoid the syrupy sentimentality of so many other movies about movies. Filho starts his film in the childhood apartment where he shot so much of his work, and then guides it outward, to the city’s once-grand downtown, studded with cinematic palaces that have mostly been repurposed into other businesses. In doing so, he gracefully reflects on the faded glories of his favored medium. —A.W.

➽ Read Alison Willmore’s full review of Pictures of Ghosts.

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell

Phạm Thiên Ân’s first feature can be elliptical to a fault in the way it chooses to unfold its story of a drifting young man named Thiện (Lê Phong Vũ) who, after the death of his sister-in-law, inherits custody of his nephew and embarks on a journey to find his brother, the child’s father. But the virtuosity of its filmmaking is remarkable, and some of the shots that Ân composed (with the help of his cinematographer, Đinh Duy Hưng) have lingered with me like persistent afterimages. In particular, there’s the sequence that starts the film, in which the camera drifts from a nighttime soccer game in Saigon, past street vendors and spectators and over to a bustling outdoor cafe where three men are talking about faith over beers until they’re interrupted by an off-screen collision. It’s impressive in its complexity and utterly haunting in its execution, as if it contains the whole world before its focus narrows in on one particular figure. —A.W.

Frida

There have been many movies about Frida Kahlo over the years, but none have given us such a sense of the artist as an actual living, breathing person as Carla Gutiérrez’s innovative new documentary. Gutiérrez, an award-winning editor, has built the movie entirely out of archival material, using Kahlo’s own words and pictures to present her life as seen through her own eyes. Thus, we hear Frida’s own achingly confessional words (spoken by Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero) as she narrates her childhood, growing up with a deeply religious mother and an atheist father; her vivacious teen years as a hip young medical student, adored by many; her lengthy, turbulent marriage to the lecherous, revolutionary muralist Diego Rivera, who overshadowed her in her time; as well as her own passionate affairs with both men and women. The director has also taken Kahlo’s drawings and paintings, including some of the most immortal ones, and animated them so that the images now shift before our eyes to reflect her emotional transformations, with pictures often mutating into one another. It’s an inspired path into the work of an artist who often painted her own visage in visually striking arrangements. By the time the movie is over, we feel, perhaps for the first time, like we’ve gotten to know this legendary, almost mythical figure. —B.E.

➽Read Bilge Ebiri’s full review of Frida.

Bilge Ebiri,Alison Willmore , 2024-06-04 15:00:00

Source link