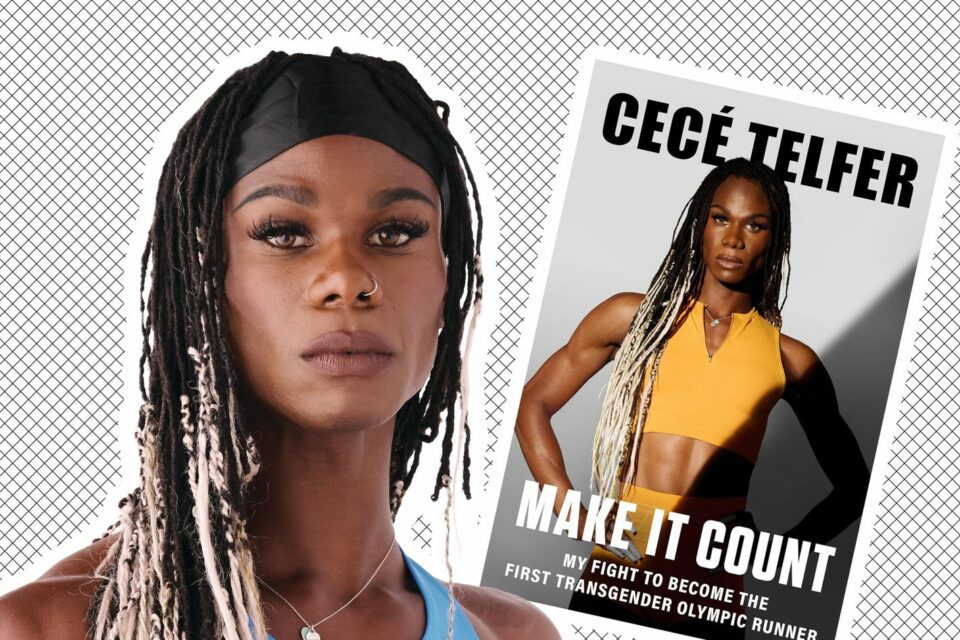

Photo-Illustration: by The Cut; Photos: Peter Yang, Retailer

Even over a grainy Zoom, CeCé Telfer’s spark is crystal clear. The 29-year-old is warm and thoughtful, often taking a moment to flick her hair off her shoulder before responding to a question. But there’s an undercurrent of heartbreak in our conversation even as we talk about her latest win — the publication of her memoir, Make It Count: My Fight to Become the First Transgender Olympic Runner, which hits the shelves today. Despite having the makings of an Olympian, Telfer is not allowed to compete in Paris.

On March 31, 2023 — Transgender Day of Visibility, no less — World Athletics, the international governing body for track and field, announced a sweeping policy change barring all trans women who had experienced “male puberty” from competition. The blow was a heavy one for Telfer, who’d already been deemed ineligible to compete in 2021 for the Tokyo Olympic trials for failing to meet controversial hormone requirements. Even before that, Telfer was making headlines as the first openly trans woman to win an NCAA title — a win the Trump administration swiftly noted, criticized, and publicly moved against.

Clearly, Make It Count is not your traditional sports story, the kind where being the best is all that counts, the finish line is the great equalizer, and everyone cheers for the underdog. “But that’s because the story of sports needs to change,” Telfer writes. Instead, Telfer offers a moving, deeply human account of her troubled childhood in Jamaica, moving to the U.S., her struggles with houselessness, and the limits of the sport she credits with saving her life as a young, isolated trans girl. And during a time when trans people, and especially trans kids, are dehumanized so regularly, Make It Count is an urgent call to recenter the needs and dignities of trans people. “I see my book as a guide for other athletes and girls that look like me and feel like they don’t have a chance, that the world is denying them at every corner,” she tells me. “I’m doing this for little CeCé — so she can see a physical manifestation of her dreams and to know she can achieve anything.”

The 2024 Olympics in Paris are now just a few weeks away. How are you handling the experience, knowing you were barred from running?

I’m very emotional because I should be at a competition right now. I should be getting ready for the Olympic trials. My heart is broken. I’m going through this process of grief and the loss of my sport … I’m trying to hold myself together.

It’s a lot to be discriminated against and to be dehumanized in front of everybody, in front of the whole world. It feels like people are letting it slide, especially the big names in sports and especially when it comes to women’s sports. Nobody’s talking about it. What are other past Olympians saying? What are other people influential in sport saying? We need to break these boundaries down. We need to have other professional athletes stand up in the face of injustice and say that the exclusion of trans athletes is not right.

Trans athletes exist, and we’re always gonna keep existing. And I know that athletics have the power to save people’s lives, especially kids. Quite frankly, being in sports right now is not safe and it’s not saving lives right now.

Are you still training?

I am still training. It’s hard for me to compete because running and competing at an elite level is so expensive and it’s very demanding.

I’ve been fighting my whole life for a coach. Ever since I graduated college, nobody has budged, no coaches want anything to do with me, but yet still, I’m still here. And I’m still the girl to beat.

Running has been such a pillar in your life. Can you tell me about your relationship to the sport?

Running for me started literally at birth. Being born Jamaican and being around the Jamaican culture, running is something that you’re born to do. I picked it up because I not only saw that it brought people together, but also because I was always bullied for being feminine and for being a girl. I was bullied really, really bad to the point I didn’t want to be here anymore.

The only thing that I wasn’t being bullied by was sports. Athletics was my shield, my protection, my armor. Athletics was my mom. It was something that protected me from this evil world and that I knew nobody could take away from me — except for World Athletics, apparently.

When I run, I feel free. I feel safe. I feel like I’m soaring. I feel protected. I feel like nothing else matters in the world because I’m here. I’m on the track. If I didn’t have track in my life, I would not be here today, period. So when I come back, I’m gonna come back not even bigger or better, but the greatest.

There’s a misconception that when people show up to their sport, it’s an even playing field. It’s not just about gender, either. It’s about class, citizenship status, the right coaches, housing security — can you talk a bit about these barriers?

I don’t think sports is an even playing field in general because you’re always gonna have somebody who’s gonna beat you, who’s better than you. But resources are a huge factor because if you have a good coach, you’re good to go. And then you have resources, socioeconomic status, time, facilities, connections, schools, mental and physical health. I don’t have a facility. I’ve been training myself. I’ve been doing everything alone that a coach, a nutritionist, a therapist should do. So why am I the girl to beat going into every track meet?

You’re overlooking all of these other females who have professional coaches, who have facilities, who have been training, who have made the team before. You’re overlooking their talent and you’re saying that I’m better than them because I’m trans. No, that’s crazy. When we are competing, when we are on that line and the gun goes off, it shows. It shows in those girls who have the coaches, have the facilities, who have been training their whole lives — they execute and they win. Yeah, we’re on the same line together, but don’t get it twisted; they have so much more of an advantage.

I’ve been fighting my whole life to be an Olympian without any resources. I have to go to competitions by myself and with the thought in the back of my mind that I might not leave this competition alive today. Right then and there, that’s a disadvantage.

What do you think needs to change so that the Olympics, and athletics more generally, are accessible?

We need bodies that represent us, that look like us, to make decisions on life changing things like sports. When we have representation, we will progress.

We’re supposed to incorporate, include, and be ready to accommodate all people in all bodies because quite frankly, I’m a woman who happened to be transgender. I’m also an elite athlete. I exist, and I’m not going to stop existing. There are girls, little girls like me that want to play sports, and they feel they can’t play because of how they look and what the world is telling them. What the world is telling them is not safe. It’s hurtful. It’s taking their lives. We need to lead with love. We need to lead with understanding.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Related

The Trans Skaters of America’s Growing Queer Skate SceneWhy Are People Mad About Nike’s Olympic Track Uniforms for Women?

Sara Youngblood Gregory , 2024-06-18 16:30:54

Source link