The closing of the Ann Nathan Gallery in River North in late 2016 felt like the end of an era. Located on Superior Street, it and an earlier Objects Gallery, both owned by Ann Nathan, had for decades been foundational parts of Chicago’s art scene and the cultural life of the city.

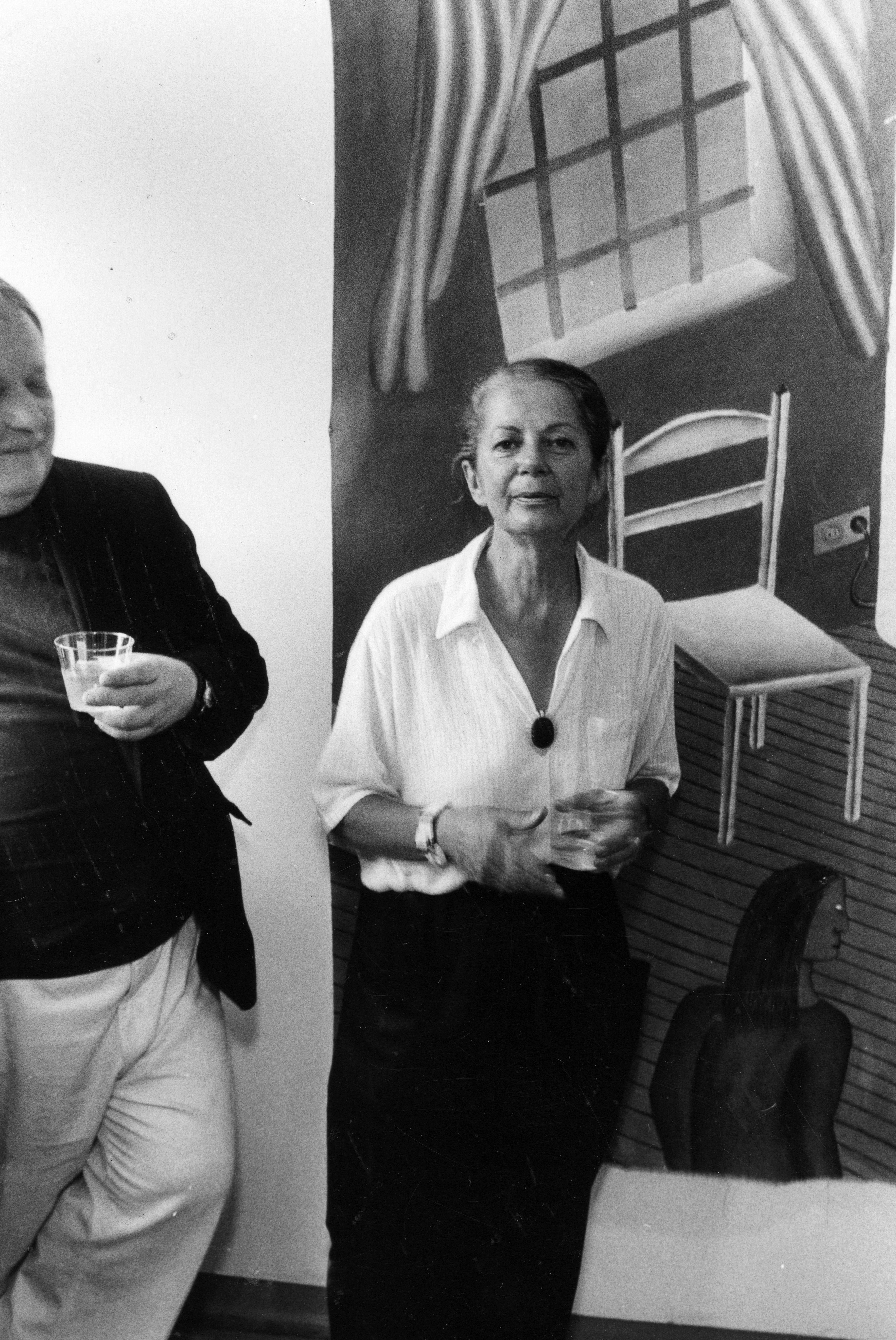

Nathan died May 5 at the age of 98. She is remembered by artists, fellow gallery owners and others for having made an indelible mark on Chicago.

In the mid-’70s, an enterprising real estate developer dubbed an industrial part of the city River North, and it grew into a hip arts-and-restaurant district. Within a decade, it hosted the largest concentration of art galleries outside of Manhattan. Opening in 1986, Nathan’s Objects Gallery was one of the first along with Zolla/Lieberman, Roy Boyd and Carl Hammer. “Ann was a fixture in River North, and her gallery important all through the years,” says Natalie van Straaten, founder of the publication Chicago Gallery News. “A stellar figure to colleagues, collectors, and artists, Ann had a unique interest in three-dimensional and figural art.”

Moreover, Nathan sold things that people could actually afford, and she represented up-and-coming creatives who were not yet blue-chip artists.

Her gallery was one of several destroyed by a devastating 1989 fire. “If I were 10 years younger, I’d go west,” Nathan told Tribune critic Alan Artner at the time. “But I am in the autumn of my life and cannot envision pioneering another neighborhood. I won’t leave the others.” She and other gallery owners found temporary quarters in the first floor of the Merchandise Mart.

In April 1993, the Objects Gallery moved to 210 W. Superior and changed its name to Ann Nathan Gallery. Hovering in an elegant, artsy space a half-story above sidewalk level, it was an anchor for the neighborhood. For many years, it was one of the stops on the popular “First Friday” events that introduced real art to so many people.

But it was a far cry from her roots as a Chicago gallerist. Nathan began in a nearly closet-sized space in the Ravenswood neighborhood, which she rented from the renowned sculptor Ruth Duckworth. That first iteration of Objects opened in 1983 — after establishing an employment agency, she gave it up in her mid-50s to open an art gallery.

Visitors to River North may remember the welcoming atmosphere of the Nathan Gallery, which was an extension of Ann’s personality. Long-time associate director Victor Armendariz remembered that she “talked with the building’s maintenance people just as she would with the wealthiest collector.” But this in no way meant that Nathan lowered her standards or her critical faculties. “Everything had to be of a certain quality, had to be serious,” Armendariz recalled, “including the people she surrounded herself with. She would even teach people how to take themselves seriously.”

Her twinkling eyes and apple cheeks belied her intense business savvy. “She was wonderfully tough,” recalled van Straaten.

In her gallery, Nathan showed a cozy medley of artists and styles — from realistic paintings and sculpture to African tribal art, from folk and what was then called outsider pieces to jewelry and ceramics. She also demonstrated a deep commitment to hometown artists. Artist Mark Bowers, one of Nathan’s rising stars, reflected, “Ann was not only my gallery owner, but a friend who pushed the growth of my art making while taking a sincere interest in my family and life.” She also supported a roster of women and artists of color long before it was popular to do so. Never a fan of pure abstraction, her galleries specialized in showing figurative and craft works. Because of this, she fostered and encouraged what has become Chicago’s signature style: Think the Hairy Who collective, Imagism and other figure-based expression.

Nathan also rejected the elitist distinction between art and design, between purely aesthetic and solely functional objects. Her gallery featured beautiful pieces of crafted furniture on which visitors were invited to sit. Another of Nathan’s contributions to art was to blur the line between styles, between media, and to flout the rules about which objects could be seen together. It affected how she lived. Those who visited her home attest to its intriguing — to some, perplexing — eclecticism. Legendary is the account of Nathan’s four-day Glencoe house sale in the late 1980s to clear the object-choked home for a move into a downtown Streeterville apartment.

Although her devotion to objects never changed, her vision for the gallery evolved over the years. Her focus narrowed from showing all manner of craft pieces to more traditional figurative art and representational artworks, including photography. Nathan’s philosophy for representing artists and selling art was simple: she took on what she liked, what she herself might have bought. “Things look at you and they speak,” she cleverly observed in a 1988 Tribune interview. “When it (a piece) starts talking to you, buy it.” Linking the artist to the viewer, she advised people to “buy from your heart, just as the artist paints from the soul.”

Many stars of figurative and narrative realistic art had their first solo shows with her, including Rose Freymuth-Frazier, Mary Borgman, the sculptor-ceramicist Cristina Córdova and art-furniture maker Jim Rose. David Becker, originally known as a printmaker, first showed his haunting paintings there. Also part of Nathan’s stable were the figurative realist Bruno Surdo and the landscape master Deborah Ebbers. Her exhibitions of the late Chicago photographer Art Shay helped consolidate his historical reputation. But not just a promoter of individual artists, Nathan was a tastemaker, too. With the painter-collector Roger Brown, Nathan was a founder of what became Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, and she encouraged other galleries to become involved as well. Sensitive to this aesthetic early on, her former Objects Gallery featured important pieces by self-taught artists like Howard Finster and now highly sought-after Southern moonshine jugs.

Nathan’s presence lives on in River North. Armendariz, her capable lieutenant of two decades, has established his own River North gallery (Gallery Victor at 300 Superior St.), which features many of the artists previously represented at Nathan’s gallery.

Towards the end of her career, she and her husband Walter Nathan stayed busy with their social and industry contacts; Walter died in 2018 after a marriage of 68 years. Ever the thoughtful curator, Ann moved things around in her own home, finding new relationships between them and bringing others out of storage to experience them afresh. She couldn’t stop appreciating things. Indeed, for many years her gallery announcements included the injunction: “Don’t stop looking at Art.”

Nathan helped teach Chicago how to look.

Mark B. Pohlad is an associate professor of history of art and architecture at DePaul University.

Mark B. Pohlad , 2024-05-29 12:15:22

Source link